Daniel, I don’t like Kung Fu: The realities of China and Kung Fu

By: Daniel Otero

Conducting a survey of 200 names on the we-chat group here in China of who studied Kung-fu or had members, family and friends who practised the art; the conclusion came back sadly and told the whole story. Out of this immense group, only three people actually still studied the art in its original form or in a hybrid state. Those who practised had been doing the art for two or more years.

One of the people I was asking about Kung-fu said and I quote, “I don’t like Kung-fu, specially when compared to MMA and Kickboxing that I’m practising now.” Therefore, he couldn’t or wouldn’t answer any questions about Kung-fu.

There is a history to this, one which has to be sincerely told. For a time, Kung-fu was banned in China. There was an entire generation which wasn’t able enjoy or didn’t know about this martial art for 30 years. Considered at one point: old, immoral and of bad influence–this patrimony of China nearly disappeared. It came back thanks to Deng Xiaoping. The art was resurrected-revived; however, with China’s new economic prosperity so focused on capitalism, Kung-fu was and has been placed aside-on the back burner-for other arts that are from abroad. The most popular arts presently in China are: MMA (Mixed Martial Arts), Taekwondo, Muay Thai & Krav Maga (Otero, 2019).

The problem with most of the youth who look at Kung-fu today, they view it as too traditional, slow and rigid to practice against the contemporary arts. Seeing Kung-fu as a relic of the past and not for real combat, which is entirely a fallacy. With MMA performances by retired-fighter, Xu Xiaodong, he gave a beat down to several Kung-fu masters in a matter of seconds. This minimized and placed Kung-fu into something shamefully of the past. And where did people go wrong? For one, Kung-fu is not to be shown for spectacles, but as a method of self-defence; which will work when practised and done in the correct way.

Kung-fu has evolved into an awesome art, but other arts need to be incorporated to get the best self-defence method and protection out of these fighting systems. Just like other arts, which are not perfect and need to be honed with other skills.

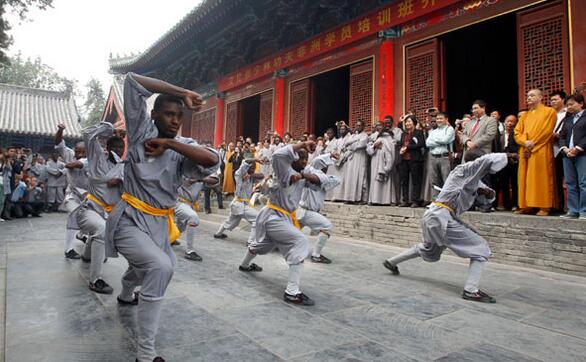

What led to the decline of Kung-fu in China has to do with historic relevance. How the art was first not allowed and then pushed aside for others arts. But it has more to do with how strict the art was to practice, secretive and how traditional masters would accept one student and reject another. Now, there is hope on the rise. Currently, Kung-fu is being brought back into public and private schools throughout the country. Other hybrid forms continue to be practised, like Bruce Lee’s ‘Jeet Kune Do’. Yes, Li Xiaolong (Bruce) continues to inspire throngs of newcomers to practise the art, whether it’s in Hong Kong or Mainland China nearly 50 years after his death. On the telly, a person any given day of the week can see a Kung-fu documentary, a children’s show inspiring kids to learn this martial art and yearly Wushu-Gong-fu competitions showcasing the best of the best in this Chinese art. Furthermore, foreigners come to China to learn the Shaolin martial-art style. So, there is still hope for Kung-fu, not only outside of China, but in the Mainland.

One of the branches of Kung-fu which continues to prosper and grow is Tai-chi Quan (Tai-ji). The older generation has carried on the tradition of going into the plazas and squares early in the morning to do their motions and keep fit! With this said, Kung-fu will never die, just evolve into something-positively better; because there is a need for it to grow and go further–so the art will not disappear.

_____________________________________________________________________

Otero, Daniel. (November 28, 2019). Thanks to Bruce Lee & David Carradine, Kung-fu did not disappear. International Journal of Martial Arts: Republic of South Korea. Pp. 1 – 16.